THE ART OF KAREN M. KRIEGER IN DREAM CATCHER MAGAZINE, EXTRAPOLATED BY GREG MCGEE

By Greg McGee

Greg McGee is Art Advisor for international poetry magazine Dream Catcher

Poets help us see the world and its incongruence. Milton lost the ability to see the words he was writing. Emily Dickinson, the master of miniature detail, lasered in on the ‘best things’, the things that are out of sight, hidden away in her ‘Best Things dwell out of Sight’, quoted here in full:

Best Things dwell out of Sight

The Pearl—the Just—Our Thought.

Most shun the Public Air

Legitimate, and Rare—

The Capsule of the Wind

The Capsule of the Mind

Exhibit here, as doth a Burr—

Germ’s Germ be where?

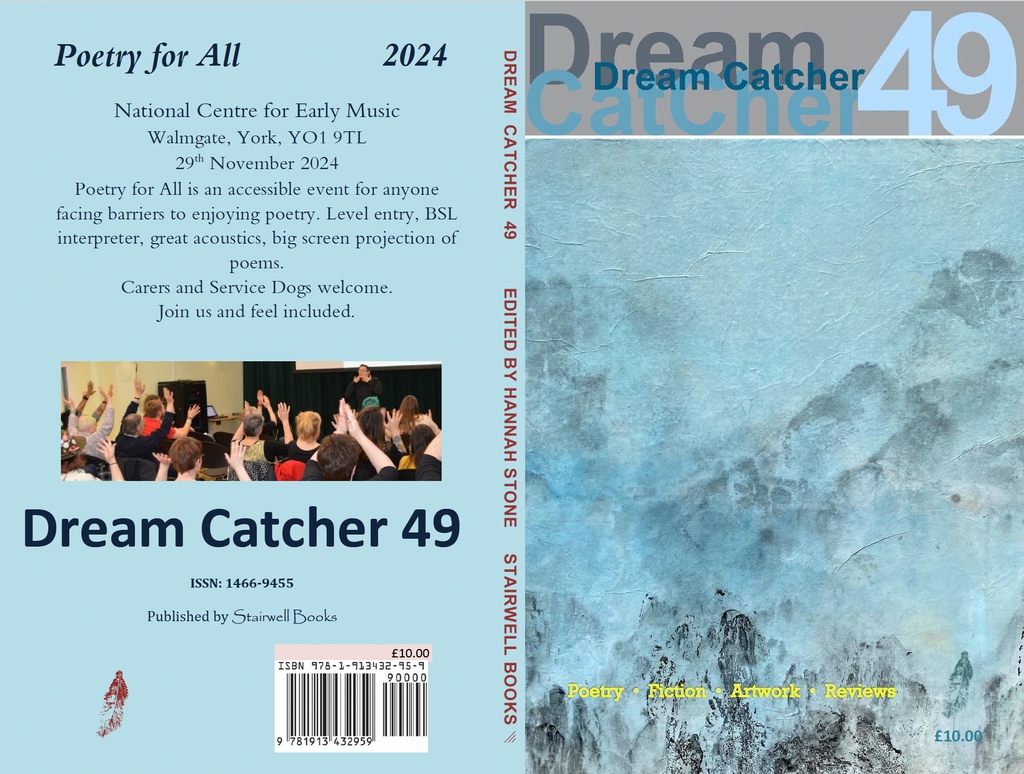

Boston based painter Karen Krieger seems to share this concern for that, though hidden, interconnects seemingly disparate aspects of the world around us: the linear and the iridescent; the edge and the cavity, the clarity and the murk. This is not to, in the style of many modern art critics, simply list dichotomous elements and sit back, basking in a bovine culturality. Krieger’s art demands more than that, as does the reader of this very poetryzine. What we’re faced with here is an invitation to make sense of the world around us, indeed to go further. When we look at something, do we really see it? In a postmodern world, where the maelstrom of visual half truths and AI generated fakes is blinding, have we learned to discriminate?

Krieger’s art, all experimental mark making and Chinese Ink, skewers the natural environment in a series of mountainscapes, opening up space for contemplation in the tradition of all the best painters and indeed poets. The goal here is not representation but rather a questioning. If we look closely at the visual surface of a mountain, why do we try and impose a monolithic quality that belies its true wriggling, water bejewelled nature? Krieger seems to have reached the same Damascus moment experienced by John Ruskin (who would have surely approved of her depictions of the natural world). In 1851 Ruskin walked through the uplands of the Jura. He finds an unexpected silent landscape, ‘no whisper, nor patter, nor murmur’. He keeps walking, over ‘absolutely crisp turf and sun bright rock without so much water anywhere as a crest could grow in or a tadpole wag his tail in.’ A rain cloud passes and drenches the waterless land, yet within an hour the rocks are dry again. He looks closely and sees, and discloses his findings in almost breathless writing. This quiet plateau he finds is riddled with ‘unseen fissures and filmy crannies’. Into these the waters vanish, and ‘far away, down in the depths of the main valley, glides the strong river, unconscious.’ Unlike many of us who see only the colour of the flags or the tribalism of people’s politics, Ruskin was achingly aware of the ecosystems that interconnect the real world, the world depicted by Karen Krieger, a world where cumulus clouds are as crenelated as the chasm they half conceal. One is not distinct from the other. The structure of the earth has a natural theology, and if you’ll allow me to stretch the point, there is more fertility in the intersection that connects us than that which demarcates.

If Ruskin was to have painted his Eureka moment his creation may have looked a little like that of Karen Krieger’s. Emily Dickinson’s ‘capsule of the wind’, hitherto unseen, is discernible in such interfusion of that which we may initially dismiss as disparity.